China builds smaller but more capable air force

The People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) has undergone two decades of transformation, trading sheer numbers for advanced technology and shifting its force structure to confront new security challenges.

A study from the National Defense University revisits earlier forecasts about the “right size” of China’s air force and evaluates how modernization since 2007 has reshaped Beijing’s aerial capabilities.

According to the report, the PLAAF in 2007 fielded about 400,000 personnel and nearly 2,700 fighters, bombers, and attack aircraft. By 2025, the force numbers 403,000 personnel with roughly 2,284 combat aircraft. The headline figures conceal a steep dip during the early 2010s, when second- and third-generation jets were retired faster than new aircraft could enter service. At one point, combat aircraft fell to about 1,500 and personnel to around 330,000.

Today, although the fleet is smaller than in 2007, it is markedly more capable. Almost all of China’s older J-6, J-7, J-8, and Q-5 aircraft have disappeared, replaced by fourth-generation Su-27/J-11s and J-10s, as well as the indigenously developed fifth-generation J-20 stealth fighter.

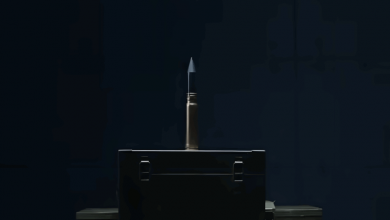

Bomber numbers have stayed roughly constant—219 today compared to 222 in 2007—but the force has improved dramatically. The H-6 family, based on a 1950s Soviet design, has been upgraded with turbofan engines, aerial refueling, and long-range cruise missile capability. The H-6N is now expected to carry both nuclear and conventional air-launched ballistic missiles derived from the DF-21. A stealthy H-20 bomber is still in development and would likely assume a nuclear delivery role.

China’s emphasis on long-range strike reflects its focus on deterring U.S. intervention in a Taiwan conflict. The report states that H-6 bombers, supported by airborne early warning aircraft, are central to China’s anti-access/area denial strategy, aimed at putting U.S. carriers and regional bases at risk.

Where the PLAAF has seen some of its most visible growth is in its support aircraft. Tanker capacity has expanded with the addition of the YY-20A fleet, including nine new aircraft in 2024. These platforms extend bomber and fighter reach, enabling regular long-range patrols. Airlift has also advanced: China now operates around 55 Y-20 heavy transports, alongside Y-8 and Y-9 medium transports, replacing older, less capable models.

Airborne early warning capabilities have surged from experimental prototypes in 2007 to about 54 operational platforms today. These aircraft now routinely support bomber missions and joint patrols with Russia. Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets have also multiplied, with electronic warfare variants of the J-16 and Y-9 joining the force.

Still, the PLAAF remains heavily weighted toward combat aircraft. Support aircraft today make up about 17 percent of the fleet, compared to 31 percent in the U.S. Air Force. Analysts note that the limited ratio of support platforms constrains the reach and effectiveness of China’s growing combat arm.

One of the most consequential changes since 2007 came from broader military reforms in 2015–2016, which reorganized the air force under theater commands. Tactical aviation assets shifted to five regional commands, while PLAAF headquarters retained authority over bombers, transports, and airborne troops. In 2023, most of the PLA Navy’s land-based aviation units—fighters, bombers, radars, and bases—were transferred to the air force, consolidating China’s coastal air defense and maritime strike missions.

These moves have expanded PLAAF responsibilities and increased its size, while aligning missions under a single command. The service now leads both territorial and maritime defense, with bombers and fighters flying regular long-range missions over the South and East China Seas.

The new analysis emphasizes that China’s aviation industry allowed the air force to avoid trade-offs predicted in 2007 between buying capable Russian equipment and relying on less advanced domestic designs. While limited numbers of Su-30s and Su-35s were purchased from Russia, most of the fleet is now domestically produced. Indigenous designs such as the J-10, J-11B, and J-20 have gradually replaced imports.

China has also fielded advanced air defense systems, with the HQ-9 derived from the Russian S-300 and produced in large quantities. Although the PLAAF still operates Russian S-400 systems, the majority of its surface-to-air missile inventory is Chinese made.

Progress in engine technology—a persistent weakness—has reduced dependence on Russian suppliers, though the transition has been gradual. Advances in China’s defense industry, combined with rising budgets, have allowed the PLAAF to procure expensive high-tech systems without shrinking overall force size.

The report highlights how unmanned aerial vehicles have become an integral part of the force. The PLAAF now operates high-altitude WZ-7s, medium-altitude BZK-005s and GJ-series drones, and has begun fielding combat UAVs for strike missions. Experiments with manned-unmanned teaming are underway, reflecting broader PLA interest in autonomous systems.

The updated analysis finds that the force is no longer the largely defensive, outdated air arm of two decades ago. Instead, it has become a modernized service with long-range strike, maritime, and electronic warfare roles integrated into its portfolio.

Authors Lauren Edson and Phillip Saunders conclude that four trade-offs—roles and missions, domestic versus foreign procurement, high-tech versus low-tech systems, and combat versus support aircraft—still offer a valuable framework for analyzing PLAAF modernization. But they add that budget growth, improvements in China’s defense industry, and perceptions of the threat environment should be treated as independent variables shaping the force.

They note that China’s relatively stable security environment allowed patience in modernization. That patience may not last.

“As U.S.–China strategic competition intensifies and the balance of regional military capabilities becomes more important, the PLAAF may be forced to focus more on near-term capability development as the risk of conflict increases,” the study says.

Future decisions will likely revolve around the mix of advanced sixth-generation fighters now in development, the introduction of the H-20 bomber, and the balance between expensive stealth aircraft and cheaper legacy platforms. Expanding the support fleet of tankers, transports, and ISR aircraft remains another challenge if China seeks to project power further from its shores.

A smaller but far more advanced Chinese air force, able to field stealth fighters, missile-carrying bombers, and modern support aircraft, is a very different adversary from the one U.S. planners assessed two decades ago.